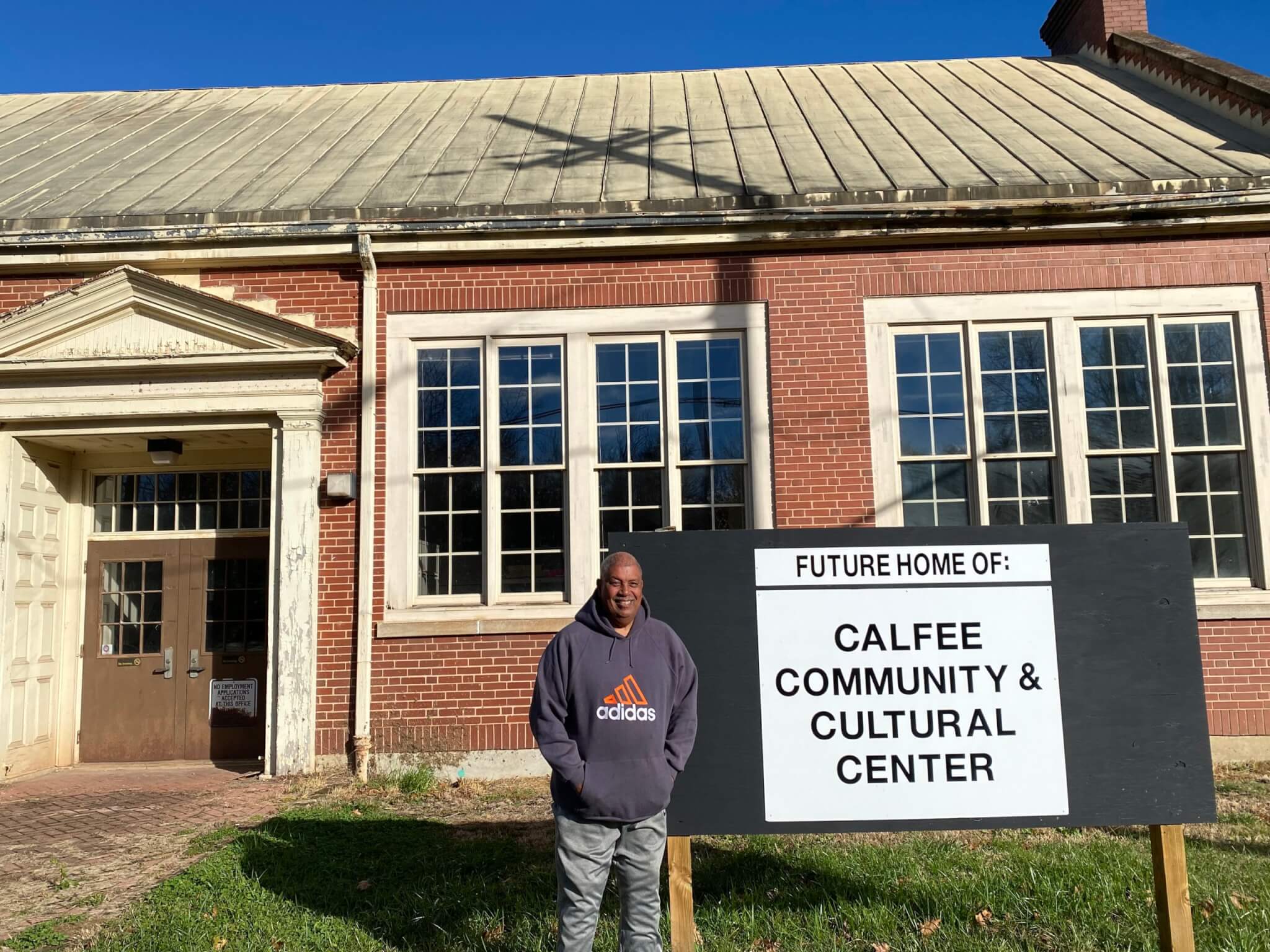

Dr. Mickey Hickman stands in front of the future Calfee Community & Cultural Center. Dogwood photo by Ashley Spinks Dugan.

Small Southwest Virginia school played a big role in the region’s history. Now officials hope it will again.

PULASKI-It’s a wintery morning in the rural Virginia town of Pulaski and Dr. Mickey Hickman is standing at the intersection of Randolph Avenue and Corbin-Harmon Drive. Suddenly, a white pick-up truck pulls up to the red light. Hickman smiles and shouts to the driver of the truck.

“Hi Scotty! We got a new street sign!” Hickman pulls out his iPhone and snaps a picture. “Look at it. It’s so shiny.”

Hickman knew the sign was coming, but seeing it actually installed was a surprise. It marked the culmination of an effort to honor two prominent Black leaders from the Southwest Virginia town, Percy Corbin and Chauncey Harmon. Hickman and other petitioners had urged the Pulaski Town Council to rename the prior Magnox Drive, a relic of a chemical manufacturing company that left the area years ago.

It’s one piece of a multifaceted project to tell the stories of Black folks from Pulaski.

History-Making Men

Stories about Corbin and Harmon intersect and overlap with those about the Calfee Training School. Black students were sent to the school prior to integration, and it still sits at 1 Corbin-Harmon Drive.

Harmon was principal at Calfee Training School in the 1930s. After arguing to the school board that his staff deserved pay equal to the local white teachers, Harmon’s position was eliminated.

“They did away with his position and all. He was a lifelong native of Pulaski and could never come back. He was only 25 years old.” Hickman added with awe, “When I was 25, I didn’t have that serious of a bone in my body. That took a lot of courage.”

Corbin meanwhile was a physician and civil rights activist. The locally renowned doctor treated both Black and white patients with a serum of his own making during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Corbin sued the school system after his son could not access the library or enroll in extracurriculars at Christiansburg Institute. Black students from Pulaski were sent to Christiansburg Institute after seventh grade. Corbin won the landmark case, a precursor to the historic Brown v. Board of Education.

‘Forced to Desegregate’

Hickman, 71, began attending Calfee Training School in 1955. He stayed at Calfee through seventh grade, and then had to make a decision. Integration had begun in Virginia. So Hickman could continue his education at Christiansburg Institute, 25 miles away, or he could go to Pulaski High School.

Hickman chose Christiansburg Institute (or “CI” as he called it)—which he figures is exactly what the white folks in Pulaski wanted.

“In the South, in Virginia, they never wanted to use that term ‘integration,’” Hickman said. “Because that meant getting along. We were forced to desegregate.”

The Pulaski County School Board had to offer the white public high school as an option, Hickman said, but “they were hoping most Black students would opt to go to the Black school.”

For Hickman, it was an easy decision. His family had a history with CI. “(My mom) was a cheerleader, dad was a football player,” he said. The kids in Hickman’s predominantly Black neighborhood of Locust Hill weren’t allowed to attend Pulaski High football games. So they traveled to Christiansburg to cheer on CI.

Going to CI meant making some sacrifices, Hickman recounted, like getting on the bus at 6:10 a.m. and not arriving at school until after 8 a.m. Only two Pulaski County buses were allocated to Black students, he said, so they took convoluted routes.

The school, like Calfee, lacked the resources of white schools, too. Hickman recalled how in primary school, students took recess in the mostly-dirt schoolyard. They had one basketball. They played football with milk cartons filled with rocks.

But in other ways, his education at Calfee and CI propelled him to academic success he’s not sure he would have achieved otherwise, Hickman said. He described an academic culture of “drill and rigor”’ at Calfee and other schools like it.

Harmon, the former principal at Calfee, attended Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, among the likes of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington. Hickman believes it shaped him, and he went on to shape the next generation of Black students at Calfee.

“Even though…we were supposed to be disadvantaged and they thought they were restricting us,” Hickman said, “In a lot of ways, just given the work ethic and the vision of a lot of these people, the leadership in these black institutions allowed us to have success.”

‘Resurrection of Calfee’

Hickman stayed at CI until tenth grade, when he transferred to Pulaski High School, he said. He attended Wytheville Community College. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Virginia Tech, a Master’s from Radford University and a doctorate in education from Virginia Tech as well. Hickman taught social studies in Pulaski County Public Schools for more than 40 years. “I’ve always been able to do the work, and I attribute it to those teachers I had at Calfee,” Hickman said.

He remembers the names of everyone who helped him get there. Soon, he hopes, their legacies will be immortalized at a new museum. The old Calfee Training School building will house the museum, part of a project that Hickman dubbed “The resurrection of Calfee.”

A 15-person board of directors, led by Hickman as chairman, has been working for more than a year to fundraise and plan for the new Calfee Community & Cultural Center. The directors are volunteers, but they’ve hired consultants, grant-writers and architects. They hope to create a place to provide childcare for low-income parents, to host events and, most importantly to Hickman, to tell the story of Calfee.

“It’s an opportunity to look at the African-American community in Pulaski, and recognize some of those achievements,” Hickman said. And they plan to tell the whole history. While they won’t “dwell on” the age of segregation, he said, it’s important context for the remarkable success of Calfee students.

Aside from touting both Corbin and Harmon, lots of other notable folks walked the halls at Calfee, he said. Leon Russell, national chairman of the NAACP, went to Calfee. Jake Carey, a member of popular 50s doo-wop The Flamingos? He went to Calfee. Neesey Payne, a current journalist with Roanoke’s WDBJ? Her father went to Calfee, of course.

“We’re a little school, but we have some things to be proud of,” said Hickman.

VIDEO: Your support matters!

Your support matters! Donate today. @vadogwoodnews Your support matters! Visit our link in bio to donate today. #virginianews #virginia #community...

Op-Ed: Virginia’s new Democratic majorities pass key bills to improve your lives, but will Youngkin sign them?

The 2024 Virginia General Assembly regular session has wrapped up. It was a peculiar session from the outset, with Democratic majorities in the...

Op-Ed: Why Virginia Needs A Constitutional Amendment Protecting Reproductive Freedom

Virginia’s recent election season in 2023 drew in eyes from all over the country. Reproductive freedom was on the line and Virginia remained the...

From the state rock to the state flower, here’s how Virginia got its symbols

Have you ever wondered why the Dogwood is the state flower? Or how the cardinal became the state bird? We’re here to answer those questions and more...

VIDEO: Second-gentleman Douglas Emhoff gives speech on reproductive freedom

Second gentleman, Douglas Emhoff touched on reproductive freedom not only being a woman's issue but "an everyone's issue" during the Biden-Harris...

Glenn Youngkin and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad night

Election Day 2023 has come and gone, and while there are votes to be counted, one thing is perfectly clear: Virginians unequivocally rejected Gov....