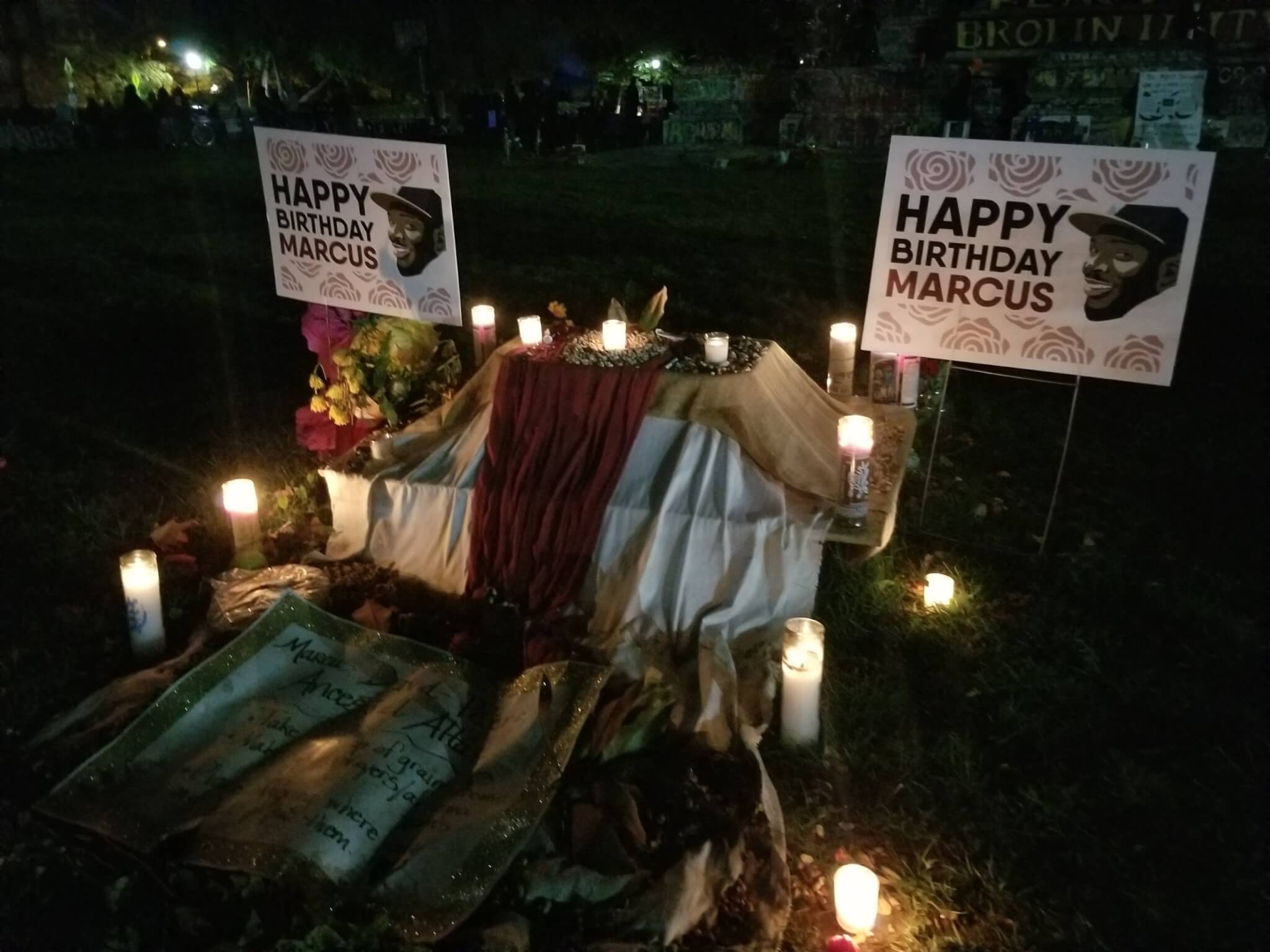

The memorial for Marcus David Peters stays up at the Circle that locals refer to by his name. Dogwood photo by Meg Schiffres.

Current version of the law is ‘dangerous and ineffective’, some stakeholders say.

RICHMOND-The Marcus Alert system was set up to save lives. However, stakeholders say the version of the bill signed by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam is both dangerous and ineffective.

“What they’ve proposed with the Marcus Alert is an offense. It’s offensive to my family and to the community who’ve been fighting for this for so long,” said Princess Blanding, Black liberation activist and sister of Marcus-David Peters.

The Marcus Alert, also known as the Mental Health Awareness Response and Community Understanding Services alert system, was crafted to protect people experiencing a mental health crisis from being killed by the police.

The alert system sets up a framework for mental health professionals and peer support specialists to respond to crises related to mental health, substance abuse, and developmental disabilities.

Demands for the alert system began in 2018, when an Essex County school teacher named Marcus-David Peters was killed by Richmond police. Peters was experiencing a mental health crisis when he was shot, completely undressed and unarmed.

Black liberation activists, including Blanding, have advocated for the Marcus Alert system since Peters’ death.

However, according to Blanding, the version that Governor Northam recently signed fails to fulfill the Marcus Alert’s mission.

“They weakened the bill but presented it to make it appear as if they really did something, that we should be celebrating. It took a lot of hard work and fight from myself, my family, and the Richmond community and supporting organizers to push this bill forward,” Blanding said.

Two Versions, One Choice

Two bills to establish a Marcus Alert system in Virginia made their way through the General Assembly.

Del. Jeff Bourne introduced House Bill 5043. This bill specified that law enforcement officers should act as backup to mental health professionals when responding to behavioral health crises.

This bill also specified several protocols that law enforcement would be required to follow. These protocols are designed to minimize the negative impact of police presence on the wellbeing of people experiencing a crisis.

Senate Bill 5038, introduced by Sen. Jeremy McPike, included a co-response model. In this version, law enforcement and mental health professionals worked together to respond to behavioral health crisis. However, this plan did not specify law enforcement’s role in the relationship.

It also did not include a number of the protocols which minimized visible police presence during a crisis. McPike’s bill also allowed localities with pre-existing mental health response programs to continue to operate those programs.

When both versions of the Marcus Alert system passed the General Assembly, a conference committee convened to consolidate the two bills into one.

“The conference report is a good combination of both the House and the Senate version. We have embedded in the conference report the flexibility that was in the Senate version for those localities that already have something similar up and running, we’ve kept the training standards, the goals, the reporting requirements and the phase-in timeline from the House version,” said Bourne.

And while that’s true, the impact of the conference report is substantially different from previous versions. By adding vague language to critical portions of the bill, some stakeholders argue, lawmakers essentially negated the system’s effectiveness.

Diversion Happens ‘When Feasible’

Previous versions of the bill define the alert system as a program that allows calls regarding behavioral health crises to be rerouted from 9-1-1 to a team of health providers. In the conference report, the definition of the alert system remains basically the same. However, the diversion of these calls to health providers does no longer happens automatically, but ‘when feasible’.

According to Blanding, the inclusion of this and other ambiguous phrases weakens the bills.

“I don’t see, the way it’s written, it rendering any different results. The language is too subjective,” Blanding said. “It’s when it’s feasible, or when the police say it’s feasible. Really? We know what the police see as feasible.”

If it is determined feasible to reroute an emergency call to health professionals, the type of care that someone experiencing a crisis receives could vary from place to place. That’s because each city and county has options to choose from.

Concerns Over Both Choices

The version of the law signed by the governor creates two response models. Cities and counties can choose which one they prefer to use.

One of these models use mobile crisis teams to respond to a situation. This team includes one or more mental health professionals but it does not involve law enforcement as part of the ‘first on the scene’ group. Law enforcement ‘may provide backup support as needed’ under this model. According to stakeholders on all sides, this is dangerous.

“[We need] to be sure that mental health professionals are not walking into a dangerous situation without law enforcement. And I think no one wants that to happen,” said John Jones, executive director of the Virginia Sheriffs’ Association. “I think it’s a danger.”

Mental health professional organizations like Mental Health America of Virginia are largely supportive of the Marcus Alert legislation. However, representatives of these groups express concern that the General Assembly rushed the concept without fully filling in the details.

“It may partly be a result of all the different revisions that were made to it. That really is one reason why I think maybe it is a good idea to take another look at it after these pilots to see what might need to be clarified,” said Mental Health America of Virginia Executive Director Bruce Cruser.

Blanding agrees. She feels this model is even more dangerous than the current method of sending law enforcement to respond to a crisis.

“If I’m a mental health professional and I’m dealing with a person who is in distress, and I see that things escalated and I need police help, now I’m calling the police to come into a situation that they have no context about. And they’re going to be very reactionary,” Blanding said. “The likelihood that they’re going to shoot to kill or strongly use police force is going to be much higher, because they’re coming into the situation from a reactionary stance.”

Richmond’s Black liberation movement, including Blanding, advocate for police to be on the scene as backup in case the situation becomes unsafe or unstable.

A Community Care Option

The other model available to localities implementing the Marcus Alert uses community care teams. Like the mobile crisis teams, these teams include mental health professionals and also may include registered peer recovery specialists.

The difference between the two models involves who can be first on the scene. Law enforcement have to be called in later as part of the mobile crisis model, but they can be part of the first response in the community care option. However, the legislation does not require law enforcement to be part of community care teams. Instead, it says they ‘may’ be included.

The community care model specifies that mental health professionals will lead the team. Law enforcement ‘may provide backup support as needed’.

However, law enforcement stakeholders hesitate to endorse this division of responsibilities.

“We’re supportive of law enforcement taking the lead in every situation,” said Jones. “If there’s a mental health call that’s not a public safety related call, then maybe someone else can take the lead. But in any situation, if law enforcement believe there’s a public safety issue, we have a duty to be there and deal with it.

Committee members also removed several reforms from the House bill that would have lessened how visible police on the scene of a behavioral health crisis are.

These reforms included prohibiting law enforcement from using marked cars and wearing uniforms when responding to behavioral health crisis calls.

Under the current bill, protocols and procedures for the Marcus Alert only consider the impact of a visible police presence. Law enforcement in this case are not required to drive and dress out of uniform.

Some Protections Get Cut Out

The House version of the bill also included language giving community care teams the authority to release someone in their care. First they would determine if that person is sufficiently stable, and then would refer them for emergency treatment services. This is cut entirely from the conference report.

Under the House bill, community care teams including law enforcement officers on those teams would be armed with nonlethal weapons. The use of lethal force would have also been prohibited. This is also cut from the conference report. The family of Marcus-David Peters and Richmond’s Black liberation movement pushed for nonlethal force to be required in these situations.

The impact and substance of the conference report differs significantly from the House and Senate versions of the legislation. However, a few specific reforms to the criminal justice system remain the same.

These reforms include a requirement that law enforcement officers utilize body worn cameras whenever they respond to a behavioral health crisis call.

The conference report also includes the creation of crisis stabilization centers, though the report does not go into detail about what those centers might look like.

Training for law enforcement on behavioral health, substance abuse, or developmental disorder-related crises is included in the final version.

“Topics such as de-escalation and communicating with individuals dealing with a mental health or substance abuse crisis are covered in the current law-enforcement minimum training standards. Currently, law enforcement officers training can vary from academy to academy, so there are no set hours for basic or in-service training in these specific areas,” said Erik Smith, manager of law enforcement, policy, and standards at the Virginia Department of Criminal Services (DCJS). “There is a 40 hour Crisis Intervention Team training that covers these areas for officers who elect or are assigned to take part in the Crisis Intervention Team program.”

However, the report does not include any mention of training for mental health professionals who enroll in the alert system.

Officials Are On The Clock

The reforms to law enforcement in the House version of the bill are not off the table. However, they may or may not become part of the alert system.

By July 1, 2021 the DCJS, in collaboration with the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS), law enforcement mental health, behavioral health, developmental services, emergency management, brain injury and racial equity stakeholders, will develop a plan for implementing the Marcus alert system.

This plan will include protocols for law enforcement agencies to enter into memorandums of agreement with mobile crisis response providers. These MOU’s will require law enforcement to respond to request for backup.

Minimum standards, best practices, and a system for the review and approval of protocols for law enforcement will also be part of the plan.

The duties that state and local entities have in implementing the Marcus alert system are included in the plan.

The conference report also directs stakeholders to include protocols for diverting calls from 9-1-1 to crisis call centers. At the call centers, these emergency calls will be answered by mobile response teams.

“A crisis call center is designated to receive calls directly from people in the public as well as referred calls from a 9-1-1 dispatch center. A call center is an essential component of the Crisis Now model, a best practice comprehensive crisis system that Virginia is seeking to emulate over the coming years. Calls are assessed and triaged by trained dispatch staff. Calls without a threat to public safety are routed to mobile crisis teams for community-based in-person response, or referred to community-based mental health providers, or de-escalated and resolved on the phone by the dispatch staff,” said Lauren Cunningham, communications of the Virginia DBHDS.

No later than December 1, 2021, five Marcus alert programs and community care or mobile crisis teams will be established. Each of these programs will be located in different regions of the Commonwealth.

For the first five alert programs, the General Assembly appropriated $3 million of its 2022 budget. The salary for staff overseeing the implementation of the Marcus Alert was also included in the budget, with $61,203 appropriated for this position in 2021. In 2022, $122,405 is appropriated for this role.

The budget also appropriates $4.7 million for mobile crisis services.

$4.7 million is appropriated to assist dispatch in implementing the alert system in 2022. On July 1, 2023, an additional five Marcus alert programs will be established in Virginia.

Another five Marcus alerts will be established in the Commonwealth every year until 2026.

It won’t be until 2026 that all localities will be required to establish a Marcus alert system.

To Blanding, waiting until 2026 is a death sentence.

“It’s ridiculous and it’s just buying time. Many people will die while we wait for that time to come to fruition,” Blanding said.

Megan Schiffres is Dogwood’s associate editor. You can reach her at [email protected].

Politics

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Trump says he’s pro-worker. His record says otherwise.

During his time on the campaign trail, Donald Trump has sought to refashion his record and image as being a pro-worker candidate—one that wants to...

Local News

Virginia verses: Celebrating 5 poetic icons for National Poetry Month

There’s no shortage of great writers when it comes to our commonwealth. From the haunting verses of Edgar Allan Poe, who found solace in Richmond's...

Join the fun: Recapping Family Literacy Night’s storybook adventures

When’s the last time you read a book aloud with a loved one? If it’s difficult to answer that question, then maybe it’s time to dust off that TBR...