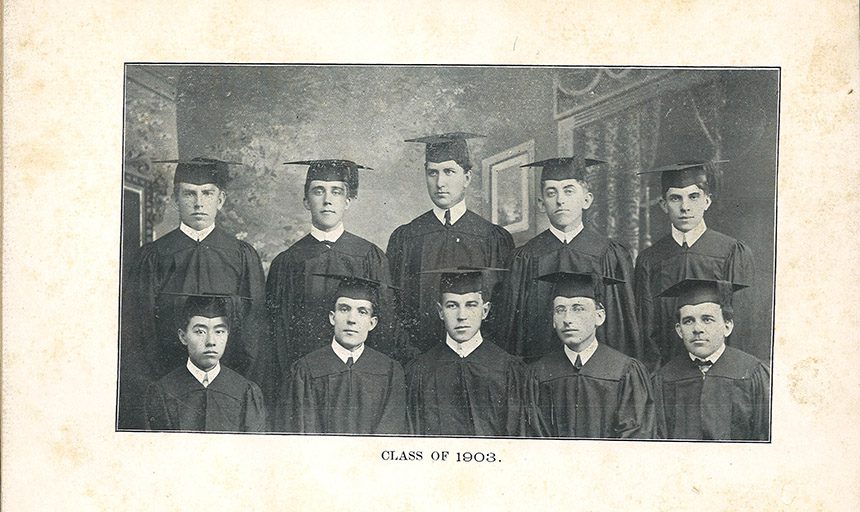

Photo used with permission from Roanoke College

May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, which honors the history, achievements, and contributions of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

This year, we’re uncovering remarkable stories of individuals who left an indelible mark on Virginia history—whether they lived in the commonwealth for years or visited briefly. From trailblazing scholars to pioneering athletes, their legacies resonate through time.

Kim Kyusik

Photo used with permission from Roanoke College

Kim Kyusik was born near Busan, South Korea, in 1881, and became an orphan at a young age. A Presbyterian missionary, educator, and translator named Horace Grant Underwood took Kyusik under his wing and taught the boy English. When he was just 16 years old, Kyusik moved to the United States and enrolled at Roanoke College.

The school’s website notes that Kyusik was “beloved socially” on campus, and “excelled academically” in his studies. He graduated from Roanoke College in 1903, and then continued his studies at Princeton University in New Jersey.

A historical marker located on the Roanoke College campus on High Street speaks to Kyusik’s influence on world affairs, noting in part: “After Japan annexed Korea in 1910, Kim served the Provisional Korean Government based in China as secretary of foreign affairs, and later as minister of education and vice president. He advocated Korean independence at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, promoted the Korean cause in the US as chair of the Korean Commission, and helped organize the Korean National Revolutionary Party in China.”

During graduation weekend this year, Kyusik’s grandchildren—Dr. Kim Soo-oak from Seoul, Korea, and Allen Kim from New York—toured the Roanoke College campus to see where their grandfather went to school. The college funds a fellowship in Kyusik’s name.

WW Yen and Hiraoaka Ryosuke

Photo used with permission from UVA Law Library; Hiraoaka Ryosuke is in the fourth row and is the ninth person from the left

Dr. WW Yen attended the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Law, where he graduated in 1900. According to a UVA School of Law article featuring 20 prominent AAPI graduates, Yen was the first international student at the Charlottesville college to earn a bachelor’s degree.

A historical marker located in Charlottesville offers additional details about his life beyond graduation.

“In the 1920s, Yen served the Republic of China as foreign minister and as prime minister, and he was briefly acting president in 1926,” the sign states. “In the 1930s, he was ambassador to the US, representative to the League of Nations, and China’s first ambassador to the Soviet Union.”

In an incredible full-circle moment in 1994, UVA School of Law Professor Emeritus George Yin became the first Asian American tenured faculty member. Yin later discovered a familial connection, which linked him to Yen.

Another international student, Hiraoaka Ryosuke, was also enrolled at the college in the 1899-1900 school year (the same time frame as WW Yen). Ryosuke was from Japan, and his name is included in the University of Virginia Catalogue printed in 1900.

Eng and Chang Bunker

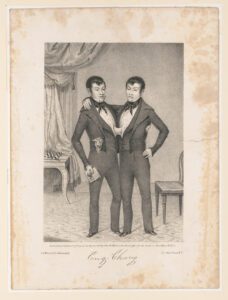

Photo by Mesier’S Lith & Mesier, P. A. (1839) and retrieved from the Library of Congress

Nowadays, the chance of having conjoined twins is one in every 50,000 to 60,000 births. It’s even more rare for the babies to be boys (about 30%), but that’s exactly what happened in the 1800s with Eng and Chang Bunker.

The brothers, born in Siam (now Thailand), were joined together at the sternum, or “breastbone.” The Uncommonwealth reported that the twins toured across the United States and Europe, charging 25 cents to anyone who wanted to see their unique physical characteristics.

The Bunkers planned to tour in Virginia, but found themselves in tax trouble at their first stop in Fredericksburg when the commonwealth imposed a $30 show license. The fee was only good for one location, meaning every city would’ve been an additional expense. Chang and Eng revised the remainder of their Virginia schedule to solely accommodate a Norfolk audience.

Once they finished with life on the road, the brothers moved just across the Virginia line to Surry County, North Carolina, near Mount Airy.

Arthur Azo Matsu

Photo included in the 1927 William & Mary yearbook, The Colonial Echo

When you think of a football player, images of Tom Brady, Cam Newton, the Manning brothers, or even Danville’s own Edmunds brothers probably come to mind. If you were alive in the 1920s, another name might’ve been on the tip of your tongue: Arthur Azo Matsu.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, to a Scottish mother and a Japanese father in 1904, Matsu and family moved to the United States in the early 1900s. By the time he was 13, Matsu was already getting attention for his athletic abilities. When the time came for him to go to college, Matsu chose William & Mary in Williamsburg, where he became the first Asian American student to play the quarterback position. He also became captain of the school’s football team, making him the first Asian American to ever earn that distinction for an American college football team. Matsu later became the first Asian American quarterback in the NFL. He also took several coaching positions, ultimately working at Rutgers University alongside J. Wilder Tasker, who coached Matsu at William & Mary.

On paper, the football player’s rise to fame looks pretty linear. The situation in the non-white community in Virginia at the time Matsu went to school in the commonwealth wasn’t as easy. From 1924 to 1930, the Virginia General Assembly passed several Racial Integrity Laws, which aimed to prevent “race-mixing” by making interracial marriages illegal, requiring racial segregation of public meeting areas, and enacting that any person with “one drop” of African ancestry was Black.

Matsu’s story was one of five that earned a coveted spot on a Virginia historical highway marker during the commonwealth’s inaugural Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month Historical Marker Contest in 2021. The contest called upon students, teachers, and families to learn more about Asian Americans that impacted Virginia, and to highlight an individual, event, or theme related to AAPI history for placement on a historical marker.

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for Virginians and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at Dogwood has always been to empower people across the commonwealth with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of Virginia families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

11 ordinary Virginians who performed extraordinary acts of kindness in 2025

Learn about some of the many Virginians who worked tirelessly to make 2025 a year that was filled with kindness. This year in Virginia proved to be...

Danville’s ‘Comeback Kid’ returns: Councilman Lee Vogler speaks after being set on fire

Three months after a brutal attack, Councilman Lee Vogler delivered a message of hope—and encouraged the community to take action. Applause erupted...

Cards for Lee: Community rallies around Danville City Councilman’s recovery

A GoFundMe page and a greeting card effort sprung up over the weekend, showing support for Danville City Councilman Lee Vogler. Following a heinous...

From hobby to herd: Southside rancher grows sustainable beef business

From offering neighborly help to running his own sustainable beef operation, Alvis White Jr. shares how he built White Wood Farm—and offers...

Local spotlight: Mayra Cordero creates custom, affordable cards in Chatham

For just $5, you can snag a beautiful, handmade card—and meet the Chatham artist behind it. It only takes Mayra Cordero a few minutes to get from...

When the storm clears: Danville-based God’s Pit Crew helps those impacted by recent tornadoes

As sirens fall silent and storm clouds move on, a different kind of force rolls in—bringing more than just supplies. “For our crew, it is a mix of...